What’s the link between these three classifications?

I can speak with authority about two of them, but I have no grounds to claim I am an athlete.

Unless … mmm, no!

At the current Paris Olympics, there has been a lot of commentary about this combination of the classifications: Women Athletes.

Firstly, there’s the furore surrounding Algerian boxer, Imane Khelif, who has been banned from competing in previous boxing championships on gender eligibility grounds but is allowed to compete at the Paris Olympics.

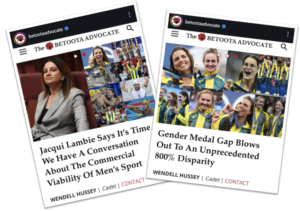

Secondly, and closer to home, there has been quite some jocularity about the gold medal performances of Australian female athletes compared to their male counterparts. So far at the Games, Aussie women have collected twelve golds to the men’s two!

The satirical news website, Betoota Advocate, among others, have even questioned whether the economic investment in men’s sporting endeavours is justified.

Humour aside, and with trepidation, I’m stepping into a conversation about gender.

It’s indisputable that gender plays a big role in the status of an athlete and their likely results. We know men’s and women’s events are separated because of disparities in inherent characteristics like strength and speed.

You may be surprised to know that in negotiation, the same holds true – inherent characteristics impact performance.

Women aren’t better or worse negotiators than men … but they have different challenges.

The factors at play are a mix of inherent characteristics and stereotypes. Girls are expected to be accommodating and relationship oriented while boys are expected to be competitive and assertive. And these expectations are normalised in negotiations.

Studies repeatedly show that women who appear to be overly assertive are frequently judged (by both men and women) to be less ‘likeable’ than women who conform to a more accommodating stereotype.

It’s a “likeability penalty” – women can be likeable or assertive but not both!

If women don’t negotiate for themselves, they won’t achieve the outcomes they desire. If they do negotiate assertively for themselves, they risk the backlash. It’s a double-edged sword.

So what can be done?

The difference in inherent characteristics isn’t the problem. Women don’t need fixing. The likeability penalty, however, does, and more people should be factoring it into their individual interactions with women.

I also think that the inherent characteristics women have as relationship builders is a vastly under-utilised advantage in negotiation. More women should learn and lead negotiations, and more leaders should harness this key resource.